Confederal Protocols: A Sketch

Federated infrastructure but user sovereignty: a “third way” between federated and P2P networksBy nullchinchilla

There are two kinds of protocols from the "open web" scene that aim to replace centralized Big Tech platforms: federated and peer-to-peer. Federated protocols, like Matrix and Mastodon, are essentially modeled after email: there are still servers and clients, but anyone can run a server, and the whole network runs off of open-source software and open standards. Peer-to-peer protocols, like Tox and Freenet, follow the BitTorrent model of there simply being peers — the end-users — that somehow collaborate to form a coherent distributed network.

With the exception of content-addressed P2P file sharing networks (BitTorrent and IPFS), the semi-successful protocols are almost all federated. Matrix (a federated protocol) may not be nearly as polished as Telegram or Discord, but at least communities of non-techy people use it — that can't really be said of P2P alternatives. We may want fully egalitarian infrastructure in which every user is a server and "every man a king", but that seems to mean tons of technical complexity and tradeoffs that nearly deny the possibility of "Web2"-like convenience.

But federated protocols don't quite cut it. To be sure, they can be pretty decentralized — there are probably more email servers than public BitTorrent DHT nodes. But we still often see the usual signs of centralization, like censorship and desperate appeals through centralized advocacy to forestall it. In practice, current federated protocols don't actually provide a meaningful leap towards the "open web" ideal of user autonomy, especially compared to security-focused centralized platforms like Signal (as Signal's founder pretty convincingly argues!). When I want to help normal folks improve their online security and mitigate mass surveillance — especially friends in China who actually need high-security communication — I recommend Signal or even Telegram rather than Matrix, since Matrix doesn't fix any problems that Signal doesn't fix under a realistic threat model.

Sovereignty, not (de)centralization

This is because nobody cares about decentralization per se. What people actually want is user sovereignty: the key security properties of the system being upheld by correct behavior of users, not third parties. For a secure communication system, that means the "CIA" triad of confidentiality, integrity, and authentication should depend only on the end users following the protocol (i.e. "end-to-end encryption"). In Signal's case, we almost have user sovereignty — as long as we trust Signal not to lie about users' public keys, not collect too much metadata, and stay online. And the problem with federated protocols is that just like Signal and other centralized protocols, we typically have provider sovereignty: Matrix homeservers, email hosts, etc, rather than users uphold the most important security properties.

But we don't need to go the whole P2P hog to get robust user sovereignty. Cryptography lets us separate who stores and routes data from who truly owns it. We can combine the easier infrastructure design of a federated protocol with the full decentralized security of a peer-to-peer protocol.

In other words, we can build confederal protocols: user sovereignty plus federated infrastructure. In a confederal protocol, there are still users and providers. But users don't belong to providers, the way they belong to web2 platforms or email hosts. They're merely customers of providers offering services like routing and storage, free to shop around and switch providers without any disruption to their user experience. You can think of a confederal network as one where every user is independent and sovereign, but free to trade and specialize without any protocol-enforced peer-to-peer egalitarianism.

| Centralized | Federated | Confederal | Peer-to-peer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure | One server | Many servers | Many servers | Just peers |

| Who is sovereign? | Provider | Providers | Users | Users |

Few federated protocols today are confederal. But there's one surprising exception: the Internet itself. Internet users usually don't self-host services, but use many different websites and ISPs, federated using a quasi-centralized naming network (DNS). Your cyberspace self does not belong to Facebook, AT&T, or the like, and you can easily switch providers — or even host your own website — without leaving the Internet. Even most P2P fans believe in the power of a confederal protocol, given that their networks still depend on the Internet.

But what would an application-level confederal protocol look like? After all, the Internet just needs to move packets, but something like a chat network needs complex abstractions — user profiles, groups, and all that.

Xirtam: a confederal chat protocol

Let's envision Xirtam /ʃɚ.ˈtɑːm/, a confederal Matrix replacement . Recall that Matrix has full-on, email-like provider sovereignty: you register an account at a homeserver, which gives you an account local to that server (looking something like @alice:aliceandbob.example.com). All your interactions with the Matrix world go through this homeserver — sending messages to other users, including users of other servers, receiving messages, etc — and the optional end-to-end encryption uses PKI controlled by homeservers. Even joining groups on other homeservers is mediated by your homeserver, which must synchronize messages with the other server, similar to how joining an mailing list works in the email world.

In Xirtam, on the other hand, there's no such thing as a "homeserver". Every username belongs in the same unified namespace (just @alice), bound globally to a public key controlled by the end user. We still have servers for hosting chat groups of all sizes, and metadata of these servers is stored within the same naming system. The boundaries of each server will probably correspond to some autonomous online community, just like a forum website, though there would probably be servers specializing in hosting general chatboards for others — the Reddits of the Xirtamverse. Users log in to a community's server by directly contacting it and presenting their globally recognized credentials.

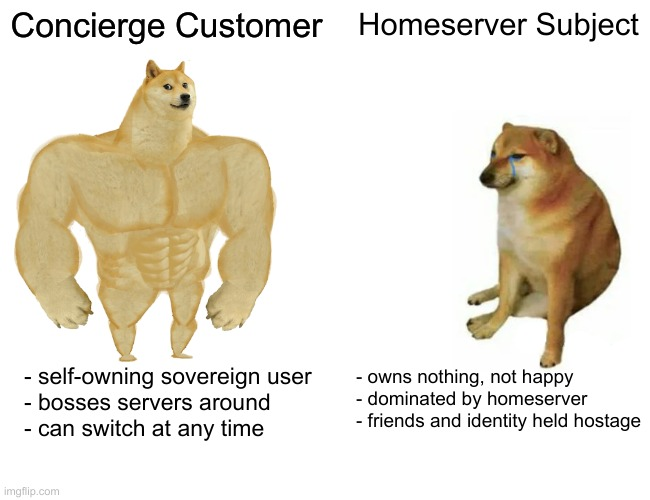

Direct user-to-user messages are handled by the user picking a concierge, a server whose job it is to backup DM history, serve user avatars, etc to people. Users advertise which server is their concierge on the global naming system; delivering messages means first finding the other user's concierge and directly pushing it a message. Concierges may also offer reverse-proxying to other Xirtam servers — a useful service for people with limited Internet connectivity who may not be able to reach all servers.

Unlike Matrix homeservers, Xirtam servers have no sovereignty to speak of. Servers do not own users, only groups, and no server can control — or even necessarily see — what a user does on other servers. Most user communities control their own servers, and even when they do not, group admins can "ragequit" an abusive server simply by uploading a backup of the member list and message history to another server and notifying all members through DM with a standardized host-switch message.

Concierges might look a little like homeservers, but unlike homeservers, concierges cannot control anything important (like the public key!) on a user's profile, and a bad concierge who censors or attacks users (say, by vandalizing their profile) will quickly fall into disuse. Switching to a better provider is just a matter of editing the namespace entry that names the concierge for a user.

Ultimately, Xirtam users enjoy full user sovereignty equivalent to using any P2P chat protocol. Confidentiality and Integrity are entirely in the hands of the user-controlled naming system, and even Availability can be secured by end users, by shunning unreliable or censorious servers.

But from the federated architecture, they enjoy many features very difficult to build in P2P networks:

- Reliable async message delivery: concierges buffer messages just like email servers do, avoiding the need to constantly be online ircd style

- Unified user and group discovery: client-side spiders crawl the global naming system, as well as the group directories of all the servers named within

- Sybil resistance and anti-spam: servers are incentivized to experiment with and evolve better, fairer policies to serve both its group and concierge customers. Users are not conscripted to be infrastructure, avoiding the perverse outcome where spamming/DDoSing a P2P network causes peers to leave and capacity to reduce rather than increase.

It wouldn't be a huge exaggeration to say that Xirtam is the "end of history" for chat apps, and confederal protocols are probably the optimal point on the centralized-to-peer-to-peer curve.

How can we build this?

So if Xirtam is so cool, why wasn't Matrix built this way? The security benefits are obvious, and Xirtam might even be simpler than Matrix to implement — there's no more complex inter-homeserver synchronization.

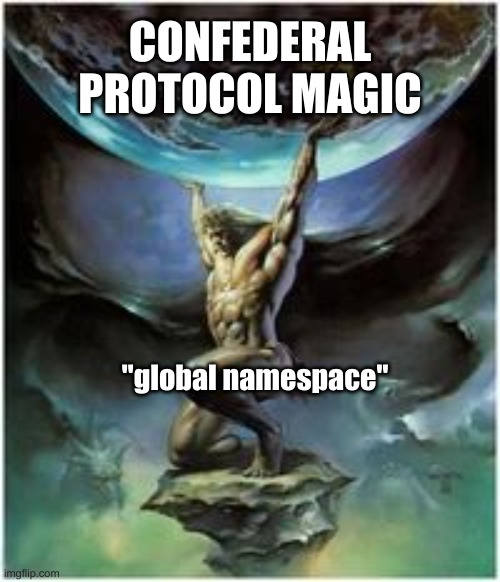

The astute reader may have noticed that one thing supports a lot of security-critical functionality — the "global namespace", queriable and editable by all users using a user-controlled keypair, and magically consistent and incorruptible despite whatever evil servers and ISPs and other gremlins may do.

Sadly, nothing like that exists (yet). It's basically distributed systems handwavium.

The obvious ways to implement this namespace are wrong:

- Centralized name directory: degenerates the whole thing back to a centralized system, where the centralized sovereignty of the name infrastructure rules with an iron fist. Good job!

- Peer-to-peer DHT of some form: this just ends up being a P2P protocol. Ensuring consistency, Sybil-resistance, availability, etc of this DHT is probably just as hard as building a P2P chat. If not actually harder — names have much stronger consistency requirements than chat histories!

The "standard" solution here is to use some sort of public blockchain. Indeed, combining user sovereignty with global consistency is the blockchain killer-app, not bonding curves or NFTs or whatever.

But before you get too excited and start loading up on bitcoins, building a reasonably usable Xirtam global namespace is very nontrivial even with blockchains. You can't just slap something on ENS and call it a day. Normal people don't enjoy interacting with crypto wallets and blockchains, let alone paying gas fees. So "just put it on the blockchain" typically means limiting the audience to serious crypto enthusiasts, which probably is an even smaller population than the Matrix-curious. And even if users do put up with the blockchain baggage, client software (especially on mobile!) would certainly not want to synchronize the whole blockchain. They'll lookup names by...calling a centralized RPC endpoint like Infura, who can arbitrarily censor or mislead users. Oops.

Fixing this needs two things:

- Trustless light clients: A way to interact with blockchain logic that neither trusts centralized endpoints nor has users synchronize the whole blockchain.

- Fully off-chain non-equivocation: A robust off-chain protocol for non-equivocating name bindings that does not require users to spam expensive layer-1 transactions for all name operations, but still inherits full blockchain security

By most measures, we are almost there. Disregarding weak subjectivity issues, how complex they are to set up, etc, Ethereum light clients like Helios get us most of the way towards 1 — sadly, most alt-L1s don't have something similar. Nobody has really built the latter yet (I tried building one on Bitcoin way back), but given the advances in fraud proofs, ZK, data availability proofs, etc, it's probably "just an engineering problem".

I think the biggest challenge left might just be a blockchain ecosystem architecture issue. Software in the "web3/crypto" space almost form a nice closed loop, where crypto tooling is "composable" iff it plugs into existing crypto tooling. Vast smart contract ecosystems sit locked behind L1s visible only through centralized RPC providers since don't even have decent light client APIs. And this problem will probably stay as long as "cryptobros" mostly build for other cryptobros rather than for a better Internet.

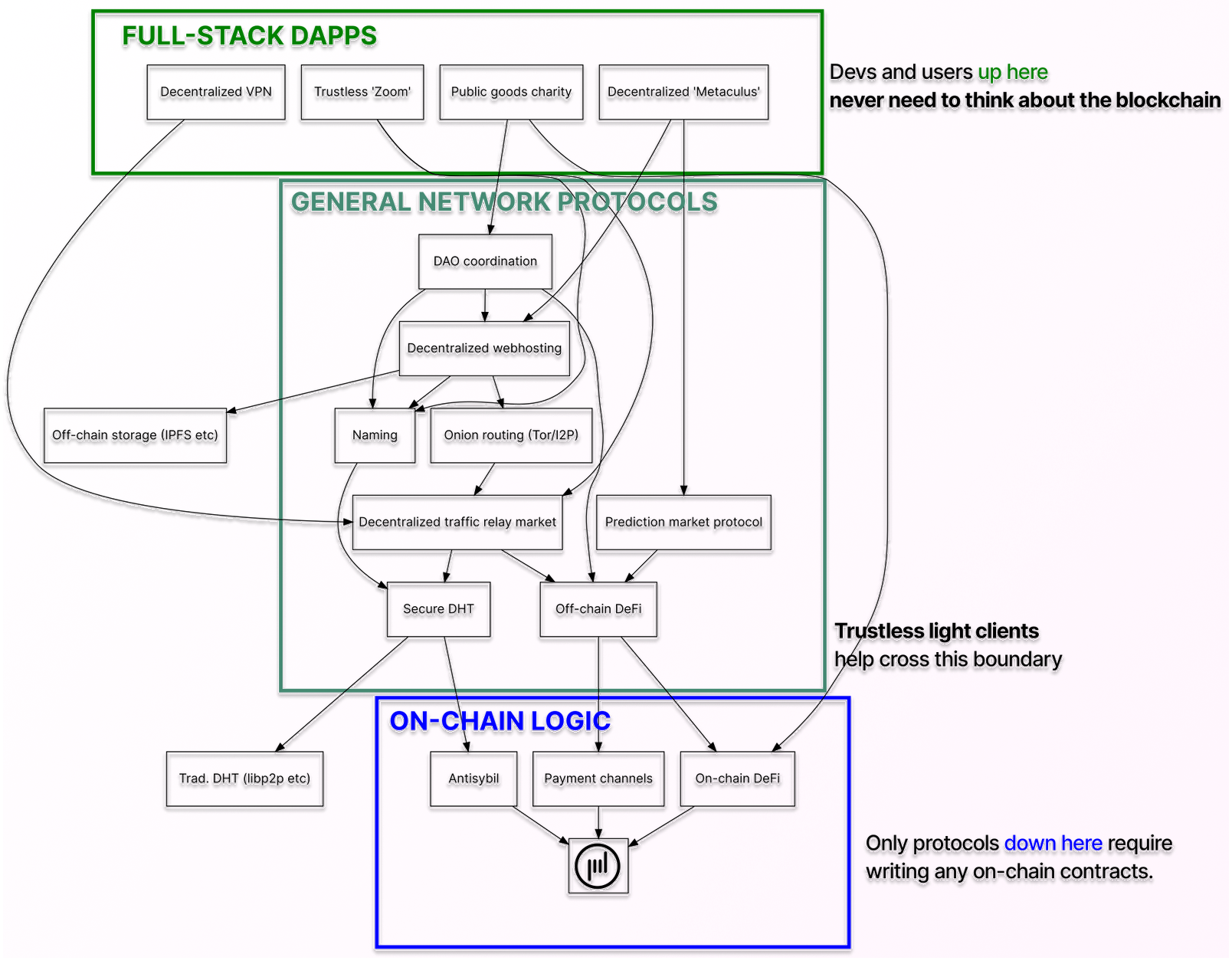

The "5-year vision" for the Mel ecosystem. Most of these protocols are confederal.

The "5-year vision" for the Mel ecosystem. Most of these protocols are confederal.As for myself, I started Mel, a project to fix exactly this architectural problem. Mel wants to build a protocol ecosystem that can actually be used for something like Xirtam, starting with an L1 entirely focused on trustless light clients that compose with off-chain decentralized protocols, but ultimately basic off-chain protocols themselves.

Once we have these building pieces, Xirtam-like confederal networks will hopefully be a clear Schelling point. Combining federated infrastructure with user sovereignty will get us a much better combination of security, usability, and ease of development than either the federated or P2P alternative.

Many thanks to nullchinchilla for allowing Black Sky Nexus to redistribute this article which was initially featured in nullchinchilla's blog on March 28, 2023.

Join Black Sky's Telegram

We consider this Confederal Protocols sketch a Post-Web design pattern. Want to find out more what we mean by the Post-Web? Join Black Sky's Telegram for a live chat Thursday June 1st at 5pm UTC.